Football is quite simple, isn’t it? Twenty-two footballers run after a ball, controlled by two linesmen and a referee, and the team scoring the most goals wins the game. Decision making in football for the past centuries was led by humans. Lately in the age of big data analytics, platform economy and real-time communication, Video Assistant Referee (VAR) has marked a turn in the way a football game is being controlled. Gone will be the intuitive frictional decision making of referees, and mistakes will be less. Let’s face it: poor human judgement and mistake can lead to the sad event of creating thousands of supporters furious in a stadium while bringing tears and sadness to hundreds of thousands worldwide (let’s not count the frustration of managers, footballers running towards a referee, the red cards, the lack of respect, the explosive post-match press conferences, etc.). Hence VAR, we were told, will remove all that; it will be an economical, financial and emotional driver to make the beautiful game… even more beautiful.

The beautiful game, VAR and the wisdom of the crowd

We are in the middle of the Champions League semifinal, between Real Madrid and Bayern München. The match is incredible. Quick dynamic, both teams are attacking, and the match is going back and forth. The fans are on fire and the atmosphere is excellent. Suddenly, the referee puts his hand to his left ear. He stops the game, does a TV sign with his hands and starts to run into the middle of the field. There is uncertainty in the environment. The incredible atmosphere is clearly broken. No one knows what will happen in the following minutes. Penalty? Red card? Even for the referee, it is not very easy to decide. He asks for the playback of the scene from different angles. In the meantime, the commentators are discussing and one of them claims: “What a bad system, look at how they broke this incredible football atmosphere. Additionally, this is clearly not a penalty” The other one refuses. “I disagree. We need the VAR; it gives us way greater justice now. Furthermore, for me, this is clearly a penalty.” Six minutes later after the referee put his hand on his ear, finally, the decision is announced. “No penalty, no red card, let us continue the game.” The fans are mad. Most of them hate the system; others love it.

VAR’s idea is to increase justice, but the cost seems high with the current system. Do we have opportunities to build a better system that can combine justice but with lower current costs? Or at least the appropriate ones? Yes, we can, and through this article, we are going explain step by step how.

What is VAR and what is its goal?

The VAR or Video Assistant Referee supports the decision-making process in a football match. It is in a centralized video operation room, which has access to all relevant broadcast cameras including dedicated offside cameras. The team consists of the video assistant referee (VAR) and his three assistant video assistant referees (AVAR1, AVAR2 and AVAR3). All video assistant referee team members are top FIFA match officials.

The main goal of the VAR is to increase justice but with low appropriate costs. Moreover, this is no different from the main objective of this article.

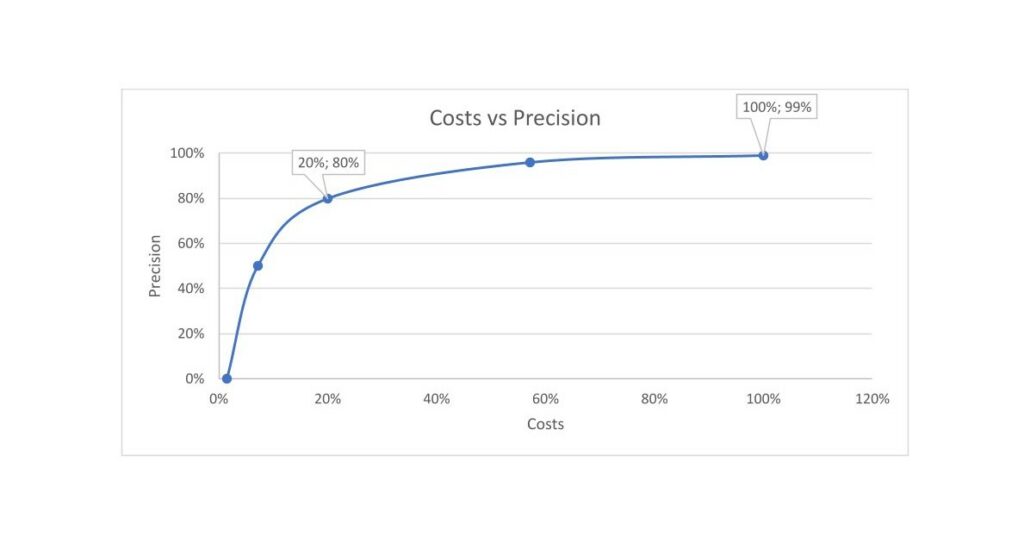

Let us take a more in-depth look into these two variables, starting with justice. How can we measure it? One good proposal will be through the precision of the VAR system. The higher the precision, the more justice we have. Now, if we want to take a look into the relationship between precision and costs, one model would be through the Pareto Principle*, which states that with 20% of one variable, in this case, the costs, we can reach 80% of the other variable, in this case, the precision. However, and unlike the Pareto principle, for our case, 100% of the costs would correspond to 99% of the precision. To reach the 100% of precision we need infinity costs. The figure would be as follow:

Two things to show through this graph:

- The first derivative is positive. It means that an increase in the precision leads to an increase in the costs.

- The second derivative is negative. It means that in the beginning of the curve, each percentage of increase in the costs leads to a bigger increase in precision. The more we are moving through the curve, the lower the increase in precision for each portion of increase in costs. In the end of the curve we need a huge amount of increase in costs to increase a small piece of precision. Every stakeholder involved in the VAR system should be aware of this sensibility of the precision and costs at the end of the curve.

Now that we define a way to measure justice and how this variable is related to the costs, let us take a more in-depth look into the costs.

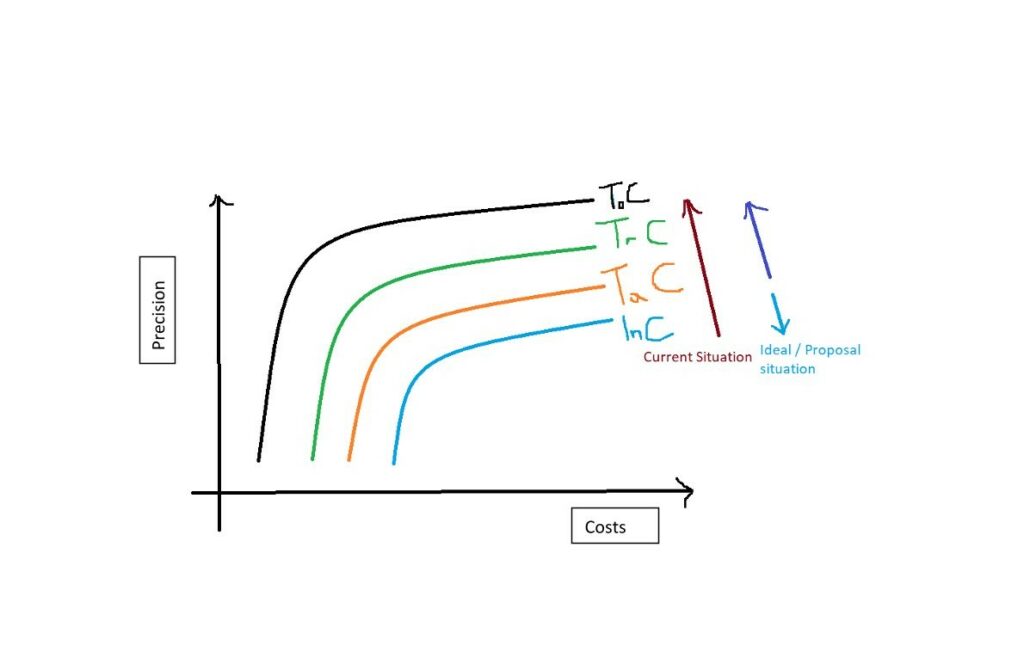

How are the costs split? The model proposed would be as follow:

Total Cost (ToC) = Intangible costs (InC) + Tangibles costs (TaC) + Training costs (TrC)

Let’s define each of them:

Tangible costs: Physical costs related to improve the system, such as equipment, technology, etc.

Training costs: Costs related to increasing the know-how of the referees and the stakeholders involved in it.

Intangible costs: Any cost related to damage the atmosphere in the stadium or the fluency of the game.

Let us dive into how this split is reflected in the curve:

In the current situation, the system is trying to move across the Total costs curve by increasing all costs. On the other side, the ideal / proposed situation is to move across the Total costs curve by increasing the Training costs and Tangible costs but reducing as much as possible the Intangible costs. This goal is the key factor to achieve the optimization of the current video assistant referee system.

Now we know where we want to go, but the logical question is, how to achieve that? Through which methodology or process? Certainly, there are different ways to achieve this. First, let us look at the current system used by the FIFA and understand where the problems are.

Current system used by the FIFA

The current system used by the FIFA can be found here. Let us go through it, step by step to understand where the problems are:

Step 1: The referee informs the VAR or the VAR recommends to the referee that a decision/incident should be reviewed.

- The referees shouldn’t inform the VAR whether an incident/decision should be reviewed or not. The VAR should do this. The referee should concentrate as much as possible to make the best intervention in the field. The VAR with all the technology, assistants and equipment, as well as by following the process model proposed, should come as fast as possible with the best output. Since the referee is number one in the review hierarchy, he can always ask for a specific review or even watch it by himself based on his criteria, but all are aware that this process should be avoided. As a result, the roles are clear, the system works efficiently and increases the precision of the system, minimizing the intangible costs

Step 2: Review and advice by the VAR: The video footage is reviewed by the VAR, who then advises the referee via headset what the video shows.

- The output from the VAR to the referee shouldn’t be an unclear advice that might be reviewed by the referee. The VAR should only interfere in the game through communication with the referee if they have a clear output to deliver.

Step 3: Decision or action is taken. The referee decides to review the video footage on the side of the field of play before taking the appropriate action/decision, or the referee accepts the information from the VAR and takes the appropriate action/decision.

- The video footage used by the main referee should be avoided. The process to review the incident and make the best decision should be done by the VAR Team, as fast and precise as possible.

Now that the issues regarding the current process has been identified, let us go through the proposed process model that can improve the current system.

Proposed model to improve the current VAR system

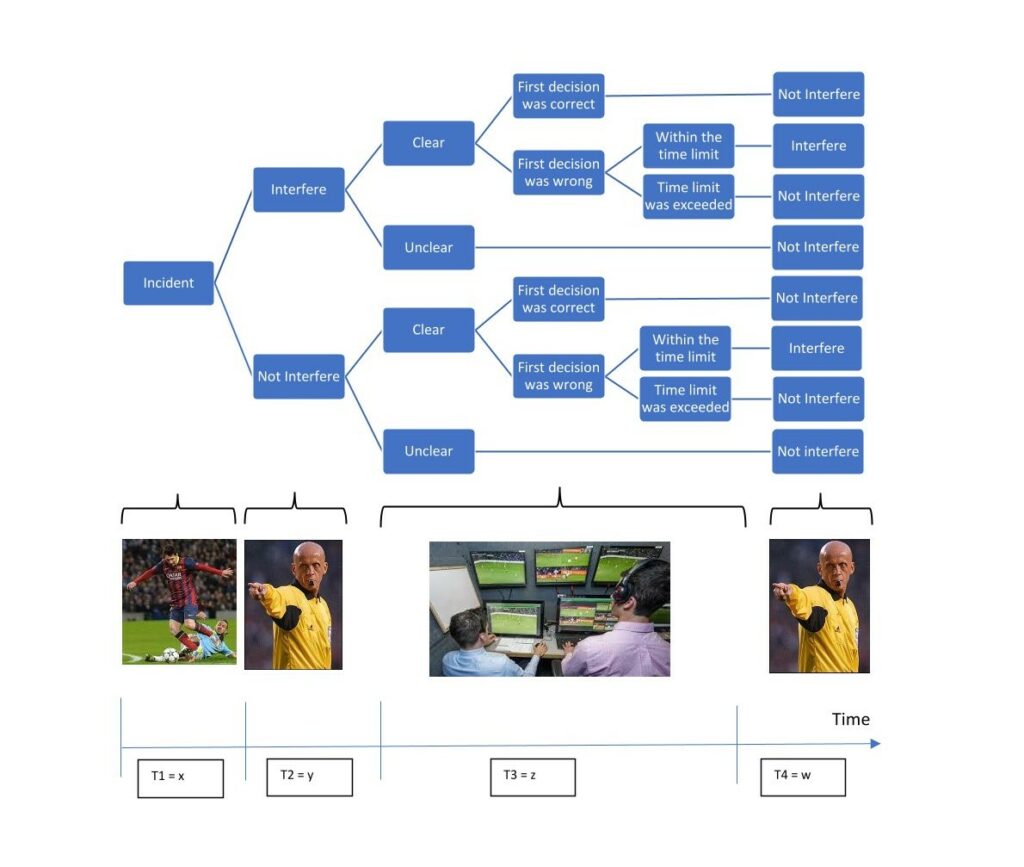

The proposed process to optimize the VAR system using decision tree model is as follow:

The following section will explain the process flow from the time of the incident to the time of the decision making, considering objects, roles, and explaining the model’s key concepts (Figure 3).

Incident: This is the first thing that happens in our process flow. An incident is any situation that occurs through the game that could be judged to make a decision. Many incidents are happening during the match. Some examples could be a foul, a hand, an offside, etc. The incidents that can be reviewed under the VAR model are restricted by the FIFA.

First referee interaction: After an incident happens, an action by the first referee occurs. The main referee has two options: either he interferes or doesn’t interfere in the game. It is essential to realize that the referee can interfere or not interfere based on an awareness of the incident. If he’s not aware of what happened, he, of course, won’t interfere. However, and regardless of the awareness, the main referee has only two options: interfere and not interfere.

Video Assistant Referee: He is sitting above the field inside the video operation room, which has access to all relevant broadcast cameras including dedicated offside cameras. He has three assistant video assistant referees (AVAR1, AVAR2 and AVAR3). All of them support and assist the referee as fast as possible. The role of the VAR should be to analyze all appropriates incidents, regardless whether the referee in the field interferes or not, and determine whether this incident is clear or unclear and produce and share an output (interfere or not interfere) to the referee as fast as possible.

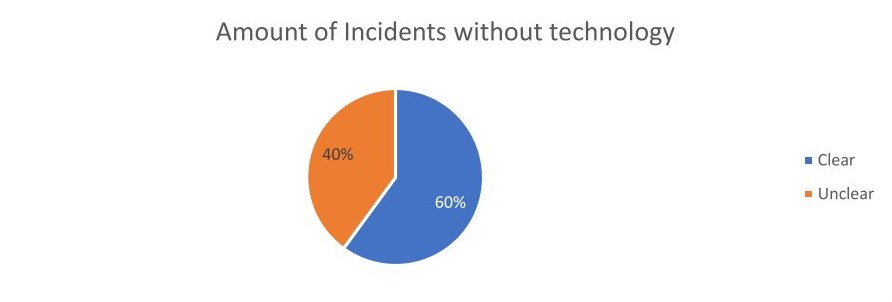

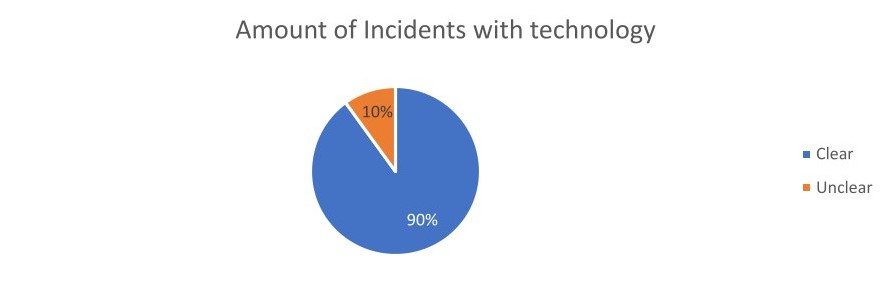

Clear and unclear incidents: A clear incident is an incident that objectively can only be interpreted in one way. On the other hand, an unclear incident is an incident that subjectively can have two or more ways to interpret, for example the situation mentioned in the introduction. These two types of incidents are one of the key separations to improve the current model. The goal is to maximize clear incident and minimize unclear incidents. Therefore, technology is one primary tool to achieve this. One example of it could be found here.

Some incidents can move from clear to unclear incidents with the help of the technology, for example, offsides, ball trespassing the goal line, or mistaken identity. On the other hand, there are some incidents that, even with the technology’s help, we cannot always move it from unclear to clear. This belongs to football’s identity/characteristics, for example, some fouls, penalties, hand balls, etc. In those cases, the judgment of the referees plays a crucial role and the proposed model protect it. To see the impact of the technology for these two types of incidents see the following figures.

Time limit: To increase the precision by increasing the Total cost and decreasing the Intangible costs (See graph 1 and 2), we need to set a time limit to move from the input to the output. The more time we use to get to the output, the more the Intangible costs. The proposal would be for 3 minutes (T1+T2+T3 < Time limit= 3 minutes <–> x+y+z < Time limit = 3 minutes). This time could be used in the test phase and adapt it regarding in the usage of the system. By introducing a time limit to define the intervention of the VAR (output), we push the system to be in a constant state of improvement (better technology, faster referee intervention, etc.), using less time to deliver the output.

The first actor in the hierarchy is always the main referee. The main referee can adapt all decisions. For example, if the time limit for the intervention of the VAR is surpassed and the main referee considers using his judgment that the VAR should interfere despite the time limit, he can always do it. The difference is that now he has a framework that he is aware of the value that it brings.

Output (Interfere or not interfere): There are only two possibilities for the output system. Interfere or not interfere (continue the game). It is essential to show how low the percentage of interfere (25% of the cases) is compared to the not interfere (75% of the cases). This is totally aligned with our main goal to increase the precision by increasing the Tangible and Training Costs but not the Intangible costs.

Conclusion and suggestions

In summary, the differences between the current and the proposal system are as follow:

- The proposed system categorizes the incidents in clear and unclear, the current system does not.

- The proposed system sets up a time limit until the output is delivered, the current system does not.

- The proposed system splits the roles of each intervention clearer and more precise compared to the current system.

- All of this leads to the proposed system increasing the precision (and therefore the justice) and minimizing the intangible costs. On the other hand, the current system is increasing the precision without minimizing the intangible costs.

Furthermore, the proposed system encourages the development of the technology and the performance of the referees in short, middle and long term to continuously improve the precision by using the Training and Tangible costs and minimizing the Intangible Costs. The development of a software and/or an app using the proposed model would be a good example.

*Kaplow, Louis, and Steven Shavell. “Any non-welfarist method of policy assessment violates the Pareto principle.” Journal of Political Economy 109.2 (2001): 281-286.